Vienna Pride 2021

at Kunsthistorisches Museum, Weltmuseum Wien & Theatermuseum

From 7 to 20 June, 2021 Pride takes place in Vienna. On this occasion, the Kunsthistorisches Museum, the Weltmuseum Wien and the Theatermuseum have assembled a diverse and queer event programme. Join us in seeing Old Masters in a new light and discover ambiguity, exceptions to the norm and eroticism where you wouldn’t typically expect them.

Pride at...

Digital content

Drag Queen Guided Tour with Tiefe Kümmernis

The drag queen Tiefe Kümmernis has been guiding a tour at the Kunsthistorisches Museum in 2019 as part of the FACES project. Her alter ego, Benjamin, is an art historian and worked with us for our education department. In this video, Tiefe Kümmernis invites you to queer explorations in the Gemäldegalerie.

Pride at Kunsthistorisches Museum...

The Kunsthistorisches Museum presents objects from five millennia – but what do they have to do with the Pride parade? One might assume that LGBTI* people have only existed for a short while and that’s why there are no related objects in historical collections. This assumption is false, however – diverse types of gender identity and sexual preferences have always existed, but without the current terminology and discourse.

*) LGBTI* = Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Intersex.

The asterisk (*) denotes that this enumeration is not definite.

Intersexuality

Intersex people are born with sex characteristics that do not match typical definitions of male or female bodies. This kind of natural variance has always existed. Mythology bears witness to that: The most famous intersex character of antiquity is called Hermaphroditus.

The term “androgynous” (from ancient greek andrógynos: “manwoman”) has often been used interchangeably with intersex. However, nowadays it is mostly found in the context of beauty ideals. In European art around 1600, bodies with androgynous looks were particularly in style. Take this painting by Bartholomäus Spranger as an example: Bacchus and Ceres, who are traditionally considered to be male and female respectively, look rather similar in this case.

Homosexuality and Bisexuality

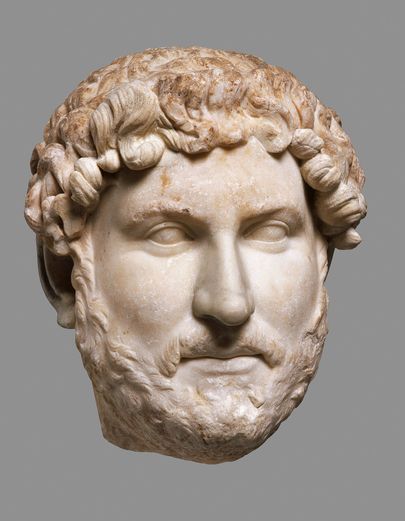

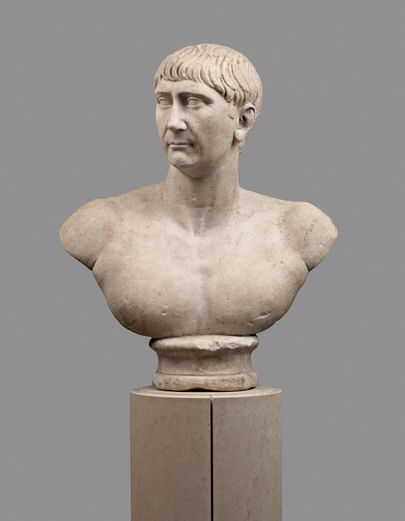

A well-known example of LGBTI* history is same-sex love between men in ancient Greece and Rome. We know of multiple rulers who both had wives and male partners who meant a great deal to them. Among them are Hadrian, Trajan and Alexander the Great. From today’s perspective, one could speak of bisexuality or homosexuality. Similar things can be assumed of women in antiquity. But they were hardly even allowed to participate in public life and that’s why the records of their sexual interests and love lives are much more scarce. Sappho is a famous exception to this rule. She lived on the isle of Lesbos (which inspired the word “lesbian”) and created poetry which described the inner and outer beauty of her female companions.

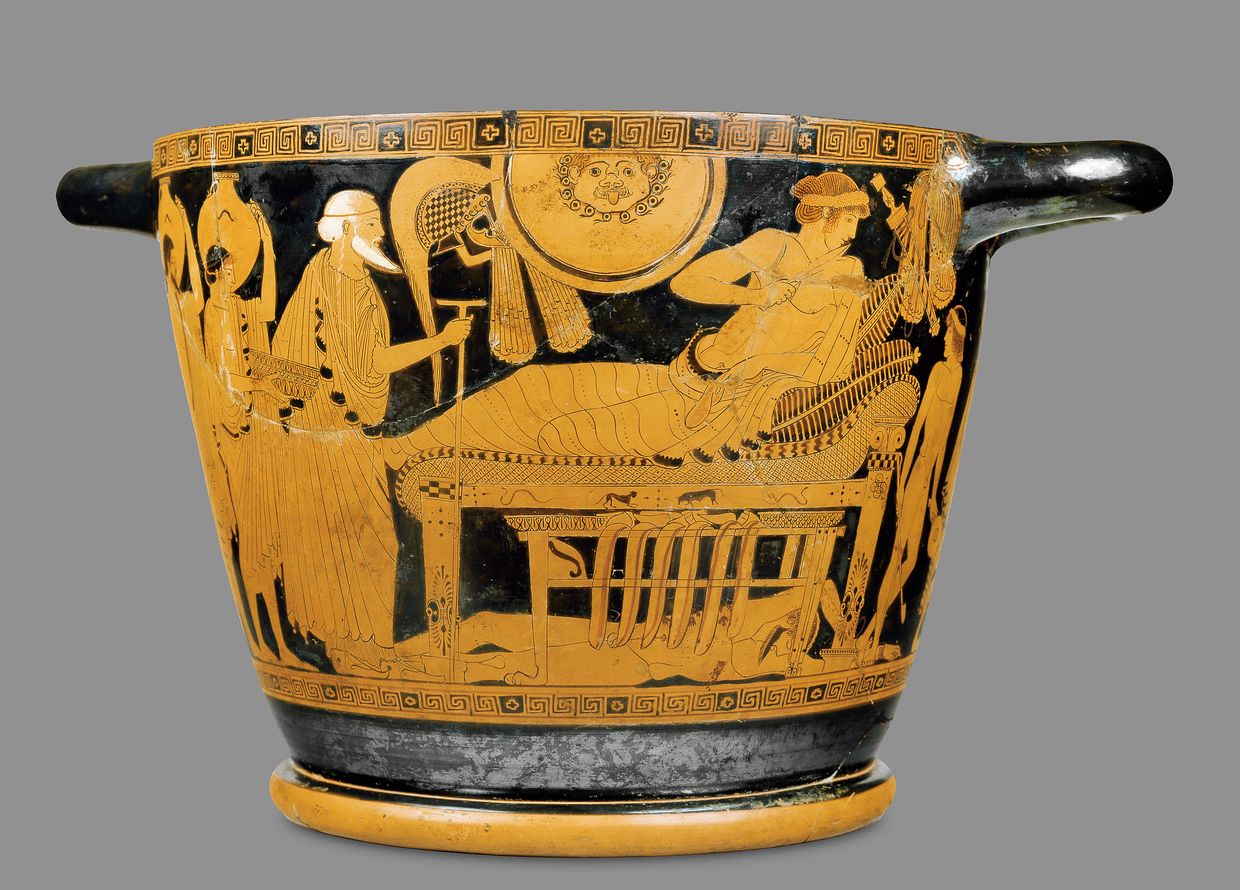

Even mighty warriors sometimes loved members of their own sex. Achilles, the legendary hero, had a partner named Patroclus. When Patroclus was killed by Hector in the Trojan War, Achilles was quick to slay Hector in revenge. On this ancient vase painting, Hector’s father is demanding the return of his son’s dead body (lying beneath the bed) from Achilles (lying on top of the bed).

There is a great deal of artists whose sexual inclinations have been speculated about even during their life time. Caravaggio, who might have been bisexual, is a notorious example of that.

You can find out more about Caravaggio HERE.

Even at the Hapsburg court in Vienna there are records of same-sex love. Isabella of Bourbon-Parma was 19 years old when she was married to the subsequent emperor Joseph II. She exchanged letters with her sister-in-law, Marie Christine, who was roughly the same age. One can gather from these letters that the two women were joined in more than just mutual admiration (“Adieu, I kiss you and worship you to a degree which I cannot express”, among many other examples).

Travesty

Men and women who swapped clothes and the transgression of socially enforced gender norms can be found in art, too. The story of Hercules and Omphale relates how the hero had to serve as a queen’s slave and how they ended up falling in love. They’re said to have swapped clothes – for their own amusement, or maybe even to spice up their love life. However, Hercules got used to his female role, which the narrative equals with subordination and depreciation. Omphale, on the other hand, had no reason for shame after swapping clothes and social roles – instead, she even gained prestige and power. One day, Hercules remembered his duties as a hero and left Omphale.

The Feminine Point of View

Time and time again, women managed to assert themselves in Europe’s patriarchal structures and become successful artists. Michaelina Woutiers from Flanders is a perfect example of that. Her Bacchanal is of monumental size, which women painters were thought incapable of creating. The painting depicts the revelry’s leader, Bacchus, not as an unsightly drunkard, but as an alluring nude in the painting’s centre. This could be interpreted as a reversal of the male (heterosexual) gaze, which otherwise rules in art history. The painter may have even included a self-portrait in the character on the right-hand edge of the canvas.

Pride at Weltmuseum Wien…

The Weltmuseum Wien is one of the world’s foremost ethnographical museums, with extensive collections of objects, historical photographs and books about non-European cultures. Among the multitude of objects from all over the world, there are many indicators of the fact that queer topics are not only a current phenomenon, but that they have been a part of various cultures for a very long time.

Bahuchara Mata

In India and other regions of South Asia, members of a third gender who are neither male nor female are called hijras. Hijras are already mentioned in the Indian myths of the Ramayana and Mathabaratha. Today, the hijra community comprises two to three million people in India and since 2009, hijras have been legally recognised as the third gender. Bahuchara Mata is the goddess of the Hijras and is worshipped by them. There are several legends about Bahuchara Mata: once the goddess was a princess who castrated her husband because he was more interested in behaving like a woman in the forest than in marital intercourse. In another story, Bahuchara Mata cursed a man with impotence for molesting her and only after he gave up his masculinity, dressed as a woman and worshipped Bahuchara Mata did she forgive him.

Tara

In scholarly Buddhism, the Goddess Tara embodies the “protective acts of compassion”. She offers protection from the dangers which seekers might face on the way to Nirvana: pride, misguidance, wrath, jealousy, fallacious ideas, parsimony, lust and doubt. For many laypeople, she is somewhat of a motherly figure when it comes to finding support for the troubles of this world.

According to the tradition of Tibetan Buddhism, Tara was incarnated as a princess, who steadfastly worked for the welfare of all sentient beings. When she reached a higher plane of existence, a sneering monk remarked to her that she could now reincarnate in a (putatively) more convenient male body, because a woman’s body was rather hindering in reaching enlightenment. The princess thereupon made a promise to always incarnate as a woman and to attain enlightenment in a female body. In Tibet, she became known as Tara the Saviouress, and offered inspiration for generations of practitioners of both genders. With her awakening, she proved that a female body can achieve enlightenment in the same way as a male body.

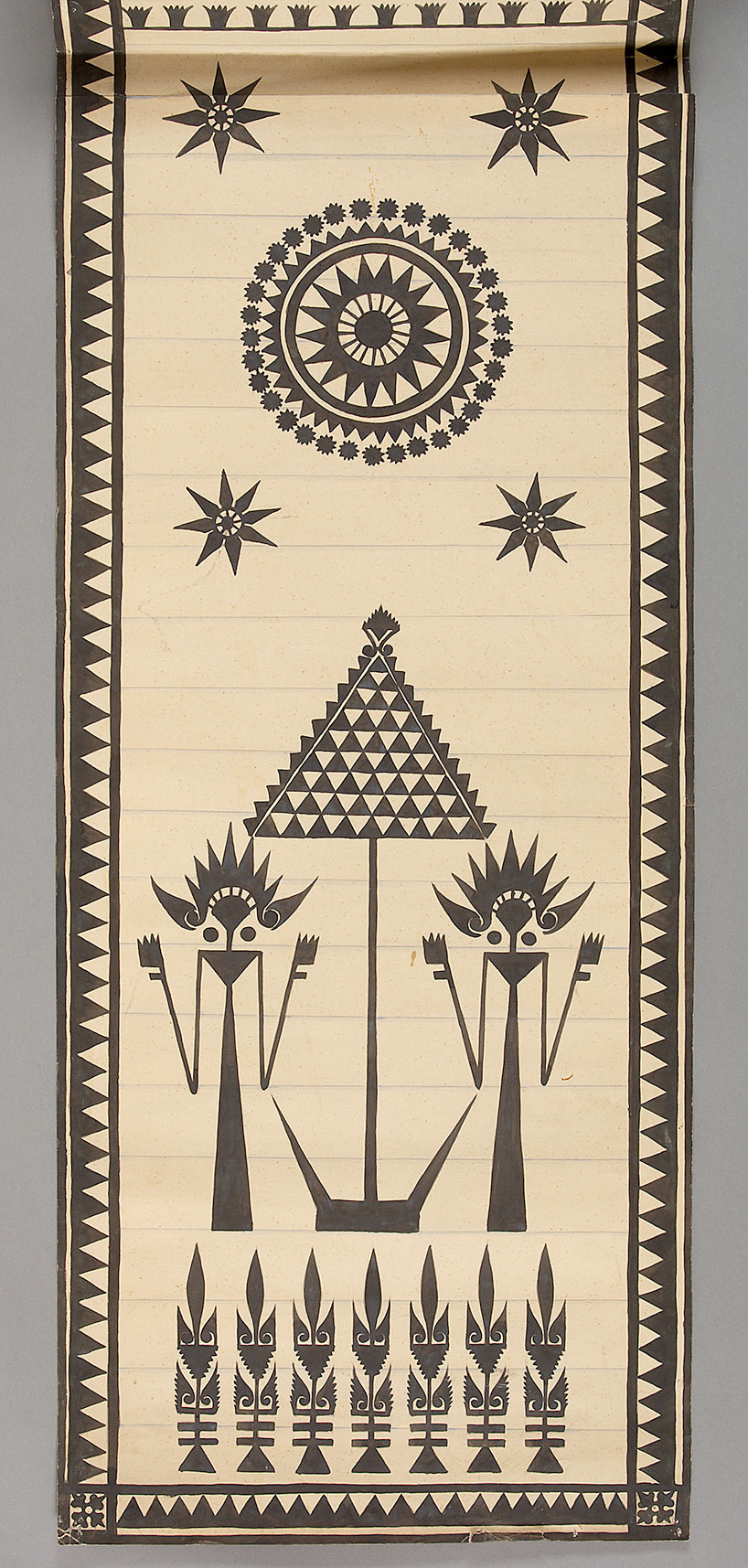

Walter Spies

The German painter, musician and collector Walter Spies (1895-1942) was one of the best Bali connoisseurs of his time. He collected the ornamented Lamak motifs and documented them with pencil and ink on paper. Palm leaf Lamak are hung in Balinese temples and are discarded when they have wilted after a few days. As a homosexual man, Spies suffered many attacks from the Dutch colonial government in Indonesia and he was arrested multiple times.

Pride at Theatermuseum…

Theatre and gender

The stage, a world of appearances and illusion: shouldn't a person's gender be irrelevant there? But a look at the theatre of the past and present shows a different picture. To this day, only two genders in stereotypical representations shape the characters in dramatic texts and their realisation on stage. A not insignificant part of this is due to the so-called "classics", which still largely determine the playbills today. In recent years, however, individual playwrights and theatre productions have increasingly dealt with the diversity of society, for example in relation to gender and sexual orientation, in order to break up the male-dominated canon. This also means that the usual hierarchies and norms in theatre are being questioned and undermined, for example through participatory working methods. New perspectives on well-known characters from the classics of theatre history, such as Hamlet or Medea, also make it possible to question preconceived stereotypical patterns and behaviour.

Who is wearing the pants here?

Trousers were already known as items of clothing in antiquity, but it was not until the 14th century that they were largely attributed to gender. Even though it was mainly men who wore trousers, over the following centuries women were in principle not forbidden to put them on as well. This only changed with the Age of Enlightenment and the rise of the bourgeoisie. The strict separation of the male and female worlds with the attributions of gender-specific characteristics was also reflected in fashion. Trousers (to be worn practically) were attributed to the (male) world of work; if worn by a woman, it was tantamount to an attack on patriarchal social structures.

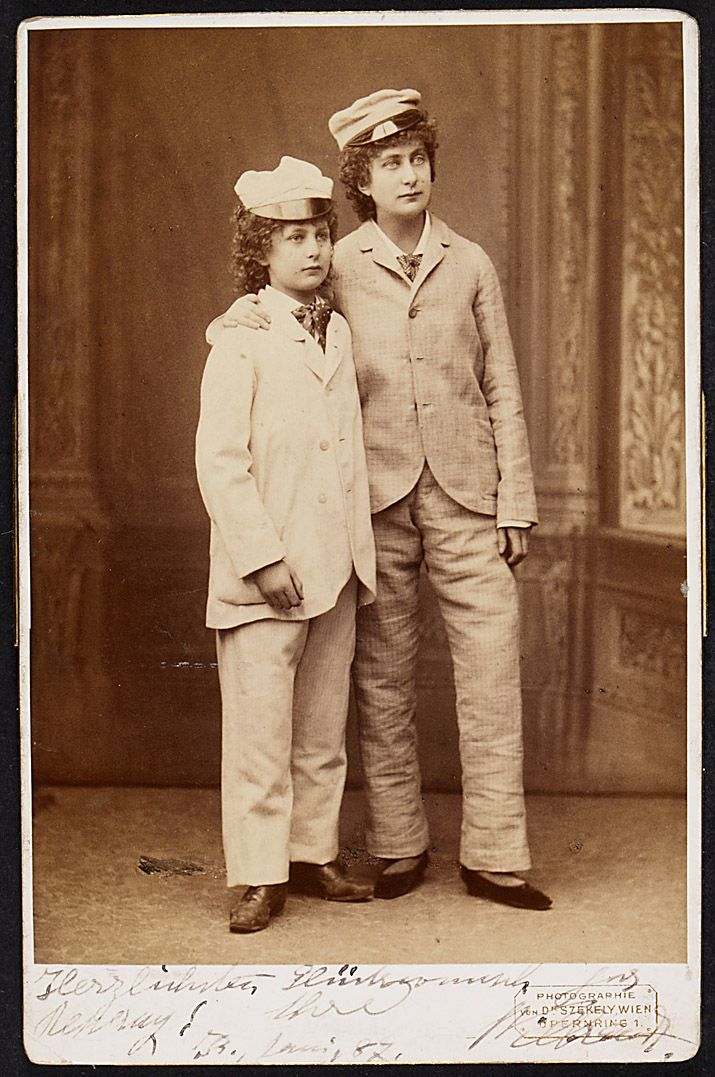

Trouser roles

Theatre has always functioned as a mirror of society. Social and political concerns - both positive and negative - have also been communicated through the stage. Socially committed playwrights who give a voice to the discriminated have always existed. For centuries, women were forbidden to perform in public; it was not until the Commedia dell'arte at the end of the 16th century that the first female actors entered the stage. Before that, women's roles were played by men. However, the emancipatory struggle was far from over when they entered the stage; appearance and dress as well as behaviour away from the theatre played a far more important role than for men. Female characters in classical plays are also mostly roles with little content and a one-sided image of women. Taking on male roles gave actresses the opportunity to show more multi-faceted characters. Wearing trousers on stage is also an attack on patriarchal social structures.

Hamlet – a lady?

Depending on the region, actresses conquered the stages in Europe from the 16th to the 18th century and soon also slipped into male roles. Hamlet has demonstrably been played by women since the 18th century. The role seems to be particularly popular because it does not embody the "typical male", but focuses on the androgynous. In the late 19th century, the image changed - Adele Sandrock, for example, found little acclaim as Hamlet. In the era of naturalism and also in the first half of the 20th century and the period of National Socialism, people wanted to see women in typical female roles. Since the 1950s, however, there have again been more female actors as Hamlet.

Fiaker-Milli

The Austrian Wienerlied singer Emilie Turecek (1846-1889) was universally known in Vienna as "Fiaker-Milli". As one of the first female folk singers, she turned the world upside down with her exuberant temperament and her breaking of taboos in amusement arcades or at balls. She even needed a police permit for her appearances in trousers, as the garment was reserved for men at the time. Her jockey costume with tight-fitting trousers, boots and riding crop caused quite a stir. At her wedding to the hackney carriage driver Ludwig Demel, the number of onlookers was so great that tramway traffic came to a temporary standstill. Emilie Demel, as she was now called, worked in her husband's carriage business and wanted to become a coachwoman herself, which was extremely unusual for a woman at the time. However, the business went bankrupt and the "Fiaker-Milli" died of cirrhosis of the liver at the age of 42, completely impoverished.

With the figure of the Fiaker-Milli, Hugo von Hoffmannsthal created a monument to Emilie Turecek in his libretto to the opera Arabella by Richard Strauss.

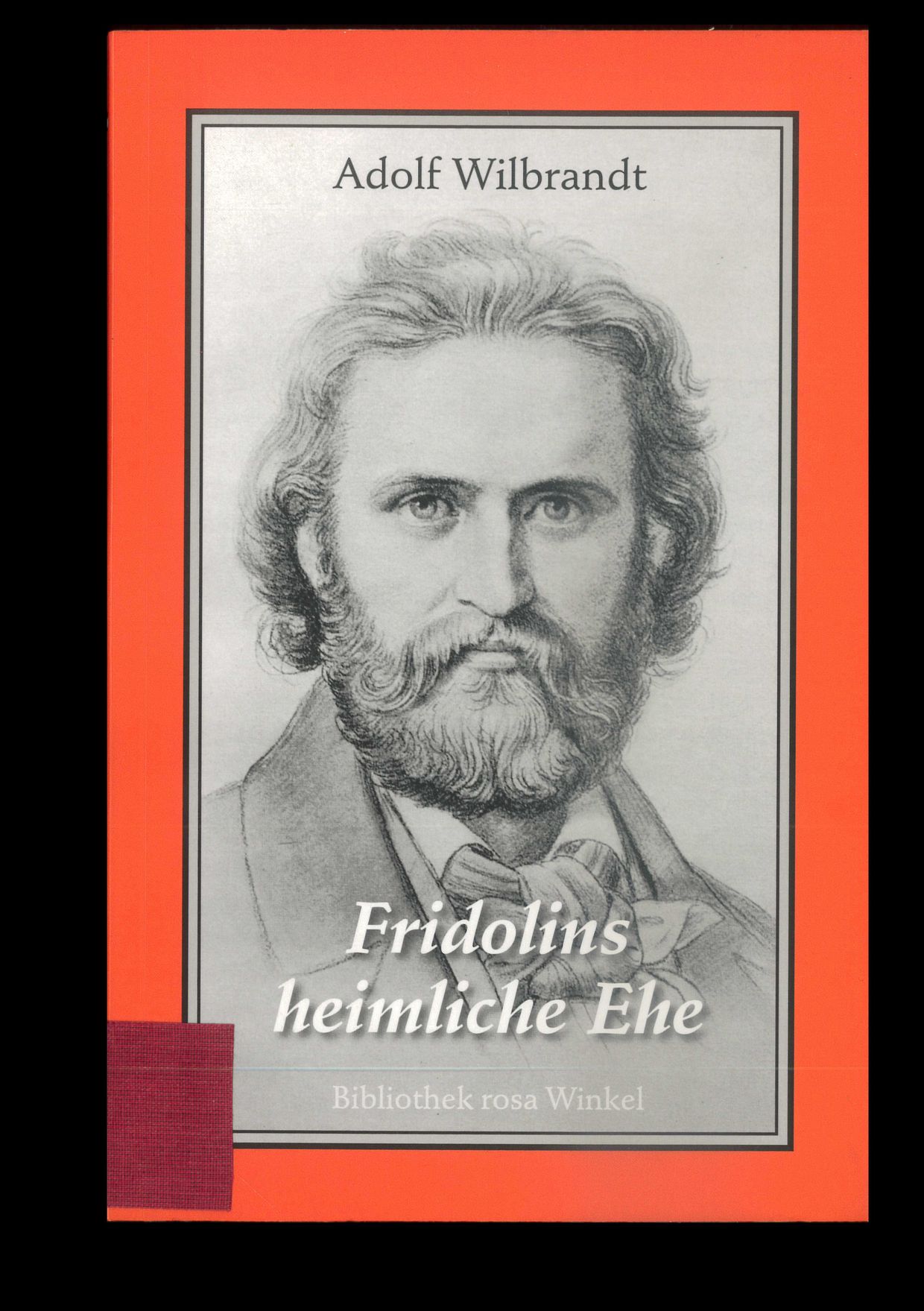

Fridolins secret marriage

Adolf Wilbrandt, a writer celebrated during his lifetime and known for his wide range of themes, as well as Burgtheater director from 1881 to 1887, wrote the story 'Fridolin's Secret Marriage' in 1875. The bisexual main character is based on a friend of Wilbrandt, the art historian Friedrich Eggers. The story was the first of Wilbrandt's works to be published in English translation in the USA in 1884 and is probably the first German-language literary text to depict a homosexual relationship. The modern term "homosexuality" did not even come into being until the 19th century, although homosexual acts had always existed, although they were not described as such. It was only in the course of establishing certain gender-specific characteristics, stereotyping and ideals that a homosexual identity was attributed as "the other", "the pervert".

Wilbrandt's narrative was far ahead of its time, which is why it was later mentioned not only in literary but also repeatedly in academic texts on homosexuality.

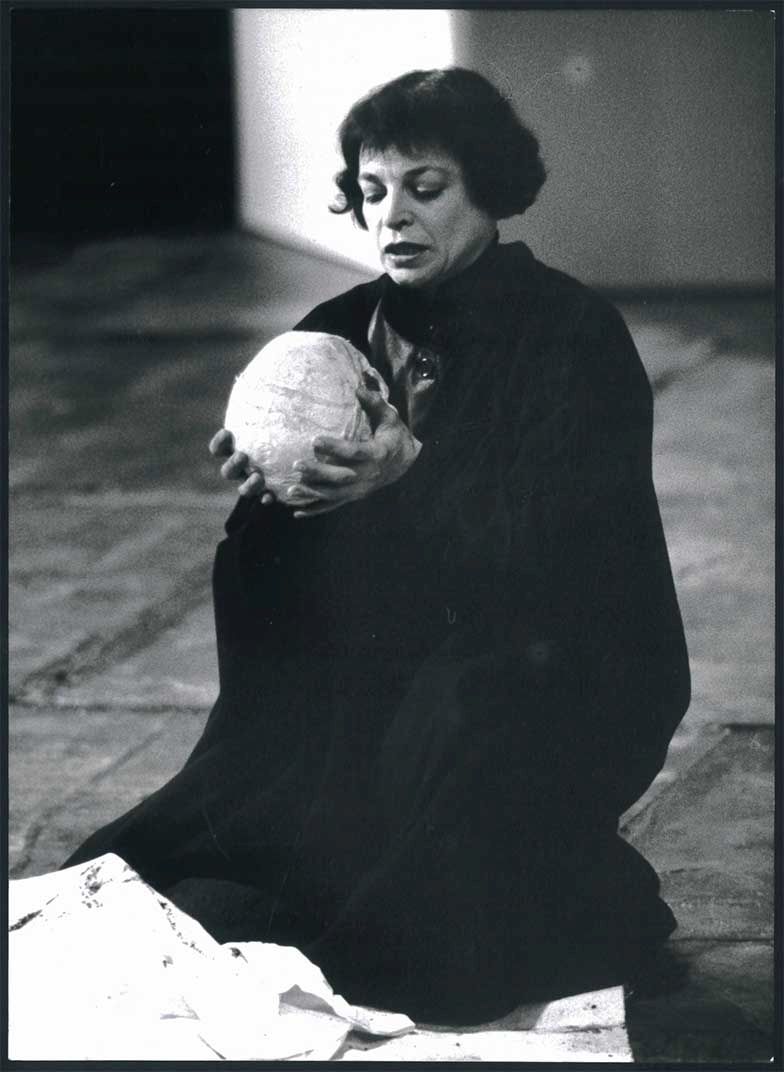

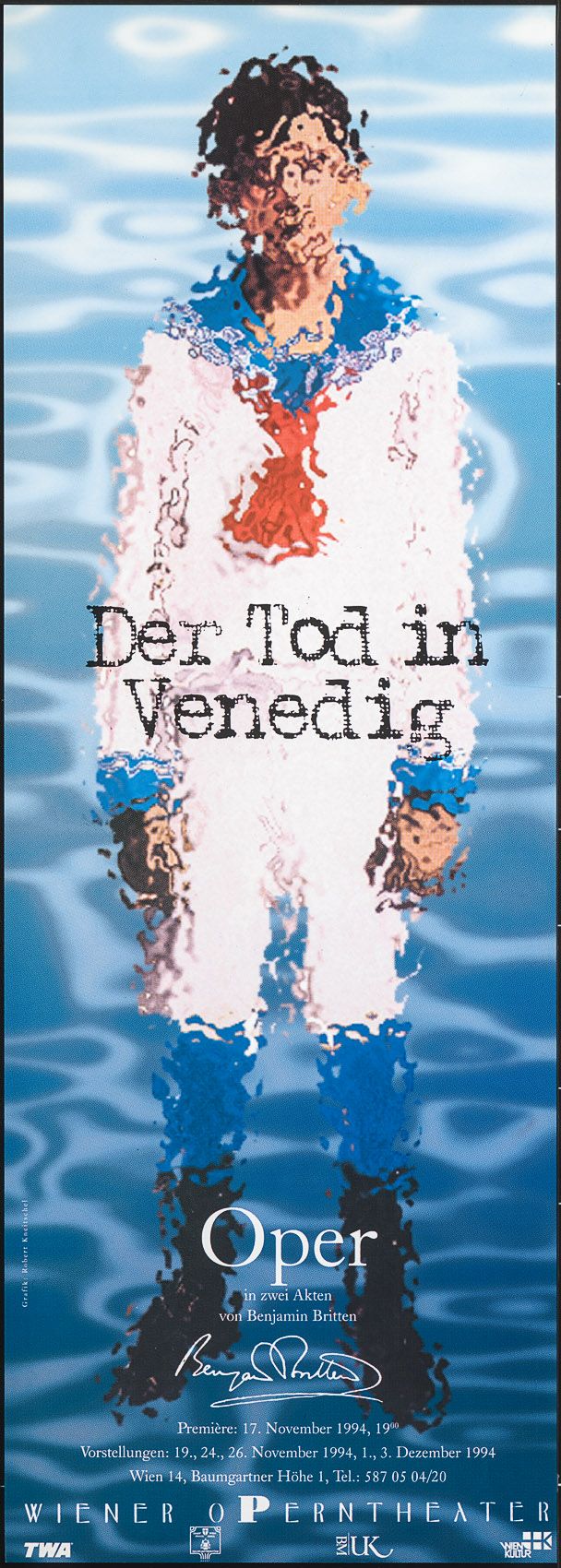

Death in Venice

Death in Venice was published in 1912 and is one of Thomas Mann's internationally most successful novellas. An elderly writer becomes obsessed with an unfulfillable love affair with a teenager, only to die as a result.

In 1971, Luchino Visconti made a film of the text, and in 1973 Benjamin Britten's opera Death in Venice was premiered at the Aldeburgh Festival in Suffolk, which he and his partner, the tenor Peter Pears, co-founded. In Vienna, the opera was performed at the Wiener Operntheater in 1994.

Benjamin Britten is considered one of the most important British composers. His best-known operatic works include Billy Budd (1951), also a setting of a novella, this time by Herman Melville, A Midsummer Night's Dream (1960) and Peter Grimes, which was first performed in 1945. The 2015 new production of Peter Grimes at the Theater an der Wien won the International Opera Award. Benjamin Britten and Peter Pears were already living together as a couple when homosexuality was still a punishable offence in Britain. It was an open secret that no one talked about. It enabled Britten to be very successful in the society of the time, to receive many commissions for compositions, to be invited to the royal family, but at the same time to create homoerotic song cycles and to give joint public performances with his partner.

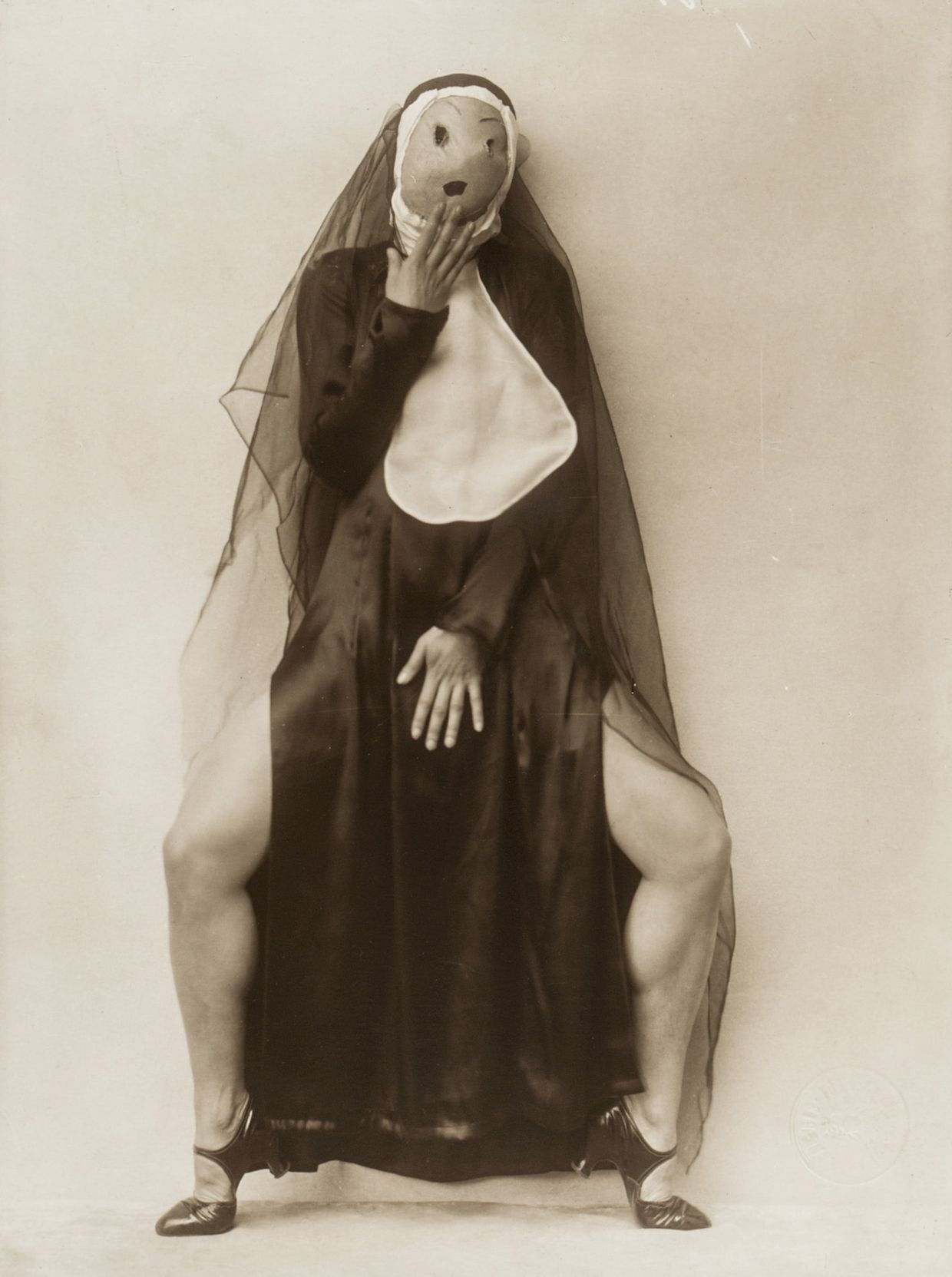

Role Models

Many female dancers dealt with given role structures and criticized gender specific role attributions. The nun is seen as embodiment of a nonsexual woman who dedicates her life to God. Hence the play with the nun’s costume is a game with female physicality and sexuality. Here we meet Mura Ziperowitsch, who by wearing a nun similar costume refers to the female corporality.

Liberation

The modern dance is also a story of the women’s emancipation. They free themselves from institutional constraints, found their own studios, become dancers, choreographers and teachers and eventually lead an independent life. The dancers overcome pre-defined structures, figures and poses of the classical ballet as well as corset and pointe shoe, dance barefoot and with flying hair.